Justice Scalia was planting the seeds that would later come to fruition in future originalist decisions produced by the Supreme Court.

Last week marked the 10-year anniversary of the passing of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. And while the Reagan appointee is no longer with us, his originalist scholarship is still influencing many of the current high court’s biggest rulings.

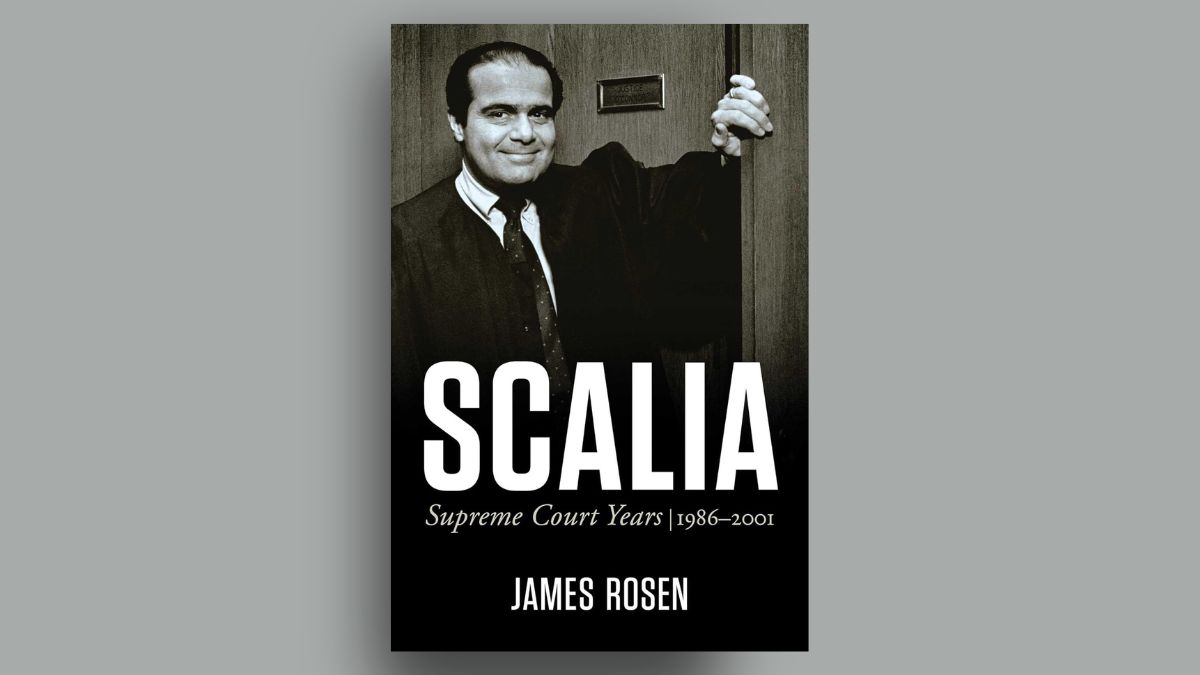

That’s the main takeaway from James Rosen’s Scalia: Supreme Court Years, 1986-2001, the newly released second volume in a three-part biographical series on one of SCOTUS’ most renowned justices. Filled with extensive research and hard-hitting analysis, the literary work represents a strong and honest counter to Scalia’s past (and more antagonistic) biographers.

As the title implies, Scalia: Supreme Court Years picks up where volume one left off and chronicles the first half of Scalia’s nearly 30-year career on the high court. Rosen documents that while the Supreme Court was not everything that Scalia imagined it would be upon his arrival (ex. hoping for more intellectual debate among the justices), the Reagan appointee’s influence was quickly felt in the court’s oral arguments, and ultimately, its decisions.

“Recounting Scalia’s early tenure on the Court, previous biographers — openly hostile to the justice and his jurisprudence — depicted him as a rude, destructive force, contemptuous of the Court’s genteel traditions, innately incapable of the hard work, nuanced and necessary, of coalition-building,” Rosen writes. “This framing of Scalia’s impact on the Court … misconstrues Scalia’s convictions, conduct, and legacy. The markers Scalia laid down throughout his tenure on the Court were never in service of declaring himself ‘more conservative’ than another justice; rather, they aimed to restore constitutional boundaries for the judiciary; a true separation of powers.”

Known as one of the chief pioneers of originalism, the judicial philosophy that emphasizes interpreting the Constitution as written at the time of its adoption, Scalia’s arrival at the Supreme Court came at a time when his style of interpretation was often in the minority. Coming on the heels of the activist Warren and Burger Courts, the justice was faced with the difficulty of originalism having to fight to establish itself as a commanding force on a court that — at the time — was averse to such interpretive methods.

Yet, as Rosen points out, even when in the dissent, Scalia left an indelible mark in his writings that laid the foundation for originalist scholarship moving forward. In many respects, the justice was planting the seeds that would later come to fruition in future originalist decisions produced by the Supreme Court.

This was evident in Scalia’s opinions in the court’s Webster v. Reproductive Health Services (1989) and Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey (1992) decisions, in which a majority of justices declined to overturn the precedent established in Roe v. Wade (1973) that invented a so-called “constitutional right” to abortion. Writing in his Casey dissent, Scalia noted that the “permissibility of abortion, and the limitations upon it, are to be resolved like most important questions in our democracy: by citizens trying to persuade one another and then voting.”

“The issue is whether [abortion] is a liberty protected by the Constitution of the United States. I am sure it is not. I reach that conclusion not because of anything so exalted as my views concerning the ‘concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life,'” Scalia wrote. “Rather, I reach it for the same reason I reach the conclusion that bigamy is not constitutionally protected–because of two simple facts: (1) the Constitution says absolutely nothing about it, and (2) the longstanding traditions of American society have permitted it to be legally proscribed.”

If such analysis sounds familiar, it’s because it was the same argumentation put forward by the Supreme Court in its 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision that overruled Roe and Casey. Citing part of Scalia’s Casey dissent, Associate Justice Samuel Alito noted in his majority opinion that “It is time to heed the Constitution and return the issue of abortion to the people’s elected representatives.”

“‘The permissibility of abortion, and the limitations, upon it, are to be resolved like most important questions in our democracy: by citizens trying to persuade one another and then voting.’ … That is what the Constitution and the rule of law demand,” Alito wrote.

[READ: Here Are 10 Great Justice Scalia Quotes To Mark A Decade Since His Passing]

While the current Supreme Court has its imperfections, much of the judicial work it produces aligns with the originalist method of judicial interpretation that Scalia championed. That is no small feat, and it’s one that the Reagan appointee deserves immense credit for.

Through his skilled penmanship and hardy legal analysis, Justice Scalia charted a course for future originalist justices to follow and pick up where he left off. And because of that, America and its Constitution are all the better for it.