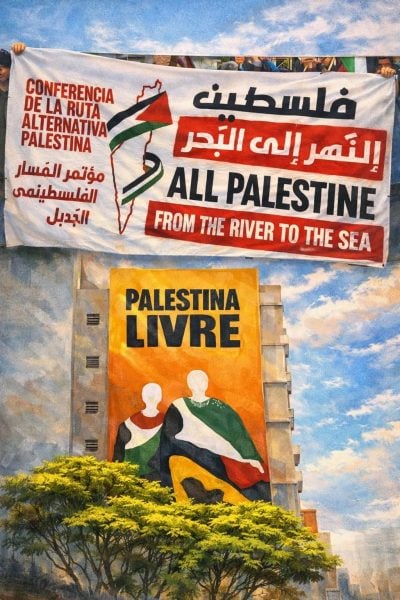

The upcoming Masar Badil conference in São Paulo (March 28–31, 2026) stands as a deliberate and audacious escalation in the Palestinian diaspora’s political struggle. In the words of founding member Khaled Barakat, it represents a “qualitative leap” into open political confrontation. By choosing Brazil — a country marked by deep Zionist economic, military-security, and evangelical penetration alongside vibrant leftist and anti-imperialist traditions — the organizers transform potential vulnerabilities into strategic advantages.

To read this article in the following languages, click the Translate Website button below the author’s name.

عربي, Hebrew, Русский, Español, 中文, Portugues, Français, Deutsch, Farsi, Italiano, 日本語, 한국어, Türkçe, Српски. And 40 more languages.

This choice capitalizes on the heightened global solidarity momentum following October 7, the powerful symbolism of Land Day (commemorated around March 30), and Latin America’s enduring history of resistance to settler-colonialism, foreign intervention, and imperialism.

In a podcast interview on Alkarama-Palestina’s YouTube channel, Samidoun coordinator Ruwaa al-Saghir (São Paulo) — joined by Khaled Barakat (Beirut) and Jaldia Abubakra (Madrid) — explained how the continent is currently witnessing a sharp rise in far-right forces, looming presidential elections, and the entrenched presence of Israeli-linked defense and surveillance firms, facial-recognition systems, and evangelical networks that extend into poor neighborhoods. Rather than shying away from these realities, the conference deliberately enters this terrain to expose Zionist infiltration, name the shared enemy, and assert that Zionism and imperialism are inseparable.

What makes the event truly bold is its refusal to treat Latin America as a mere backdrop for distant solidarity. As al-Saghir describes it, the conference offers a chance to restore the voice of the Global South — to forge a living bridge between the Palestinian struggle and the ongoing fights of Brazilian, Argentine, Chilean, and Venezuelan peoples, drawing on five centuries of shared colonial dispossession, indigenous resistance, and anti-imperialist memory. In a region still scarred by the memory of military coups and facing renewed U.S. threats against Venezuela, convening such an event is itself an act of political defiance, turning the diaspora from a passive support base into an active frontline.

Masar Badil actively conducts multilingual outreach to expand its reach, especially among younger diaspora generations who may not speak Arabic fluently. The movement draws strength from its proven networks — Samidoun for prisoner solidarity, Alkarama for women’s organizing, and various youth structures — which have mobilized hundreds of events, protests, and webinars since 2021.

Ideological Clarity and Its Strategic Tensions

Ideologically, Masar Badil offers uncompromising clarity. It rejects the Oslo framework, the Palestinian Authority’s security coordination with the occupier, and the mainstream two-state paradigm, instead positioning Palestine as the vanguard of a global anti-imperialist struggle. This stance draws in activists disillusioned with moderate or institutionalized approaches, offering a radical alternative.

As Khaled Barakat reminded listeners, the October 7 operation and the genocidal response that followed have imposed new priorities on every Palestinian current: the urgent, practical work of stopping the slaughter, flooding the streets, universities, and unions, and raising slogans once considered marginal — “Long live October 7,” “Long live the armed resistance,” “From the river to the sea.” The São Paulo conference carries this shift forward by calling openly for popular rebellion against a Palestinian Authority that coordinates security with the occupier, marginalizes the resistance, and imposes recognition of Israel as a condition for political belonging.

This embrace of October 7, however, creates a strategic tension: how to defend the principled right to armed struggle — a right affirmed in international law and repeatedly recognized by UN General Assembly resolutions, yet systematically criminalized by Israel and the United States as “terrorism” — while building the broadest possible internationalist coalitions needed to confront genocide and imperialism. For many potential allies on the global left, or among those horrified by the destruction in Gaza, unequivocal celebration of the attack can appear deeply challenging, not because armed resistance is inherently illegitimate, but because decades of Israeli and U.S. propaganda have successfully framed any endorsement of Palestinian military action as moral transgression.

Masar Badil appears to resolve this tension by refusing to dilute its political clarity, insisting that genuine awakening requires confronting uncomfortable realities rather than conforming to externally imposed red lines. Whether this unapologetic stance ultimately expands or limits the front of solidarity will be tested in spaces like the São Paulo conference, where the movement seeks to mobilize diverse actors under its banner.

Jaldia Abubakra underscored another dimension of this courage: the insistence that women and youth — especially those born in the diaspora — must occupy central, non-decorative roles, changing stereotypes and mobilizing entire communities in languages and spaces that official politics often ignore.

Repression, Internal Dynamics, and the Vanguard Question

Central to the movement’s self-understanding is its transformation of repression into validation. Organizers view every sanction, arrest, travel restriction, funding block, and lobbying effort to cancel events not as setbacks, but as evidence of real impact. As they have stated repeatedly, “every repressive step only ignites greater determination.” The intensity of the response — from U.S. and Canadian designations to German bans and personal sanctions on leaders — demonstrates that Masar Badil is disrupting financial flows, narrative control, and diaspora passivity in ways that genuinely threaten the Zionist project and its backers.

Even the challenge of remaining a minority voice within the broader pro-Palestine spectrum is reframed as a strength. By refusing co-optation and openly competing with official Palestinian diplomacy and more moderate solidarity groups, the movement claims authenticity as the genuine revolutionary path — untamed and therefore worthy of suppression.

Masar Badil’s portrayal of repression as validation, while powerful from the movement’s perspective, invites closer scrutiny of its strategic trade-offs. Vanguardism may forge a highly committed revolutionary core, but it often comes at the expense of broad-based appeal. By treating virtually all compromise or institutional engagement as co-optation, Masar Badil risks political sectarianism — potentially narrowing alliances with more moderate pro-Palestine forces and obstructing the diverse, majoritarian coalitions historically essential to successful decolonization struggles. Is isolation truly evidence of vanguard efficacy, or might it limit the movement’s capacity to scale mass mobilization at a time of genocide and deepening global polarization?

The organizers would likely counter that genuine mass awakening demands uncompromised clarity rather than strategic dilution, and that the post-October 7 transformation of global discourse — where slogans once deemed marginal have gained widespread traction — already demonstrates the effectiveness of their approach. The continued — and even expanded — planning of the conference in early 2026, despite layered sanctions, high-profile arrests (such as that of executive committee member Mohammed Khatib in Greece), and persistent Zionist lobbying efforts to disrupt venues, stands as the clearest validation in the organizers’ narrative. The São Paulo conference will serve as a real-time test of this tension: whether bold, confrontational organizing in contested terrain can expand solidarity, or whether it ultimately reinforces the movement’s position on the frontline margins.

Theory of Change: Means, Ends, and the Path Forward

Masar Badil’s vivid emphasis on defiance, advance, and the transformative power of conferences and networks radiates inspiring energy, yet it leaves a deeper question hanging: what is the concrete theory of change? If the explicit goal remains full liberation of Palestine from the river to the sea — rejecting two-state diplomacy, Oslo compromises, and the Palestinian Authority’s framework — how precisely do diaspora-led initiatives translate into tangible shifts on the ground? How do they strengthen steadfastness in Gaza and the West Bank, empower Palestinians within the 1948 borders, or erode the occupation’s material foundations?

The organizers would likely respond that consciousness-raising, the forging of unified resistance fronts, and sustained international pressure constitute indispensable preconditions for any breakthrough, especially after decades of failed diplomacy. They might point to the October 7 rupture as already demonstrating how armed initiative, when backed by popular and global support, can fundamentally alter the equation. Without a clearly articulated pathway linking diaspora vanguardism to the daily realities of those under siege, however, the globalized project risks remaining more aspirational than operational — more a powerful moral and ideological rallying point than a fully elaborated strategy for decisive victory.

The São Paulo gathering, through its workshops and joint declarations, will provide one concrete measure of whether this approach can forge genuine connections between the diaspora’s activism and the homeland’s endurance— or whether the gap between rhetoric and on-the-ground impact endures.

In the end, the São Paulo conference embodies the movement’s deepest conviction: when empires tighten their grip, the revolutionary response is not retreat, but a bolder, more internationalist advance — turning the adversary’s chosen ground into the next arena of struggle.

*

Click the share button below to email/forward this article. Follow us on Instagram and X and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost Global Research articles with proper attribution.

Rima Najjar is a Palestinian whose father’s side of the family comes from the forcibly depopulated village of Lifta on the western outskirts of Jerusalem and whose mother’s side of the family is from Ijzim, south of Haifa. She is an activist, researcher, and retired professor of English literature, Al-Quds University, occupied West Bank. Visit the author’s blog.

She is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

Featured image is from the author

Global Research is a reader-funded media. We do not accept any funding from corporations or governments. Help us stay afloat. Click the image below to make a one-time or recurring donation.